Robert M. Cutler

Indian stocks market followed the global sell-off in March 2020 that resulted from covid- and lockdown-inspired risk aversion, as New Delhi initially followed global policies. The lockdowns severely diminished demand for goods and services, creating economic uncertainty. It also exacerbated supply-chain disruption, complicating business operations. Declines in global oil prices that year also caused profits of Indian companies in the sector to fall. The Bombay Stock Exchange (BSE) benchmark, the Sensex index, suffered its sharpest decline since the 2008 global financial crisis, falling by 30 percent, as the figure immediately below shows.

As is immediately clear from the chart, however, the Sensex recovered well from the 2008 global financial crisis. By 2011–2012, it had begun to form an ascending channel that lasted through the rest of the 2010s. It briefly broke through the channel’s lower support after the artificial shock of the government lockdown in 2020, but it began to recover as the lockdown was partially lifted. When the Indian government fully lifted the lockdown in late 2020, the Sensex then threw a leg over the channel’s upper resistance and escaped it. Since 2021, it has been in another ascending channel, much narrower than the original one, but parallel to and above it.

This week I will delving in greater detail into the Indian equity markets, in the articles available by subscription only. The detail will include sectoral breakdowns with individual equity highlights, including in the natural resource sectors. However, it is important first to survey the country’s basic macroeconomic situation.

Inflation in India has been relatively low lately, but it is expected to rise, mainly due to rising commodity prices and increasing demand. In recent months, the Reserve Bank of India (RBI) has been raising interest rates in the attempt to moderate inflation. In the short term, this will have a relatively negative impact on the equity prices, but in the longer term, in combination with other factors, it will contribute to greater economic growth.

Inflows of foreign direct investment (FDI) into the Indian economy have been strong, signifying international confidence in the Indian economy and in its future. FDI is expected to continue to increase in coming years. India’s current account deficit (the difference between imports and exports) is relatively small, and this is expected to diminish further in the future. That would mean that its external borrowing will also diminish, other things being equal.

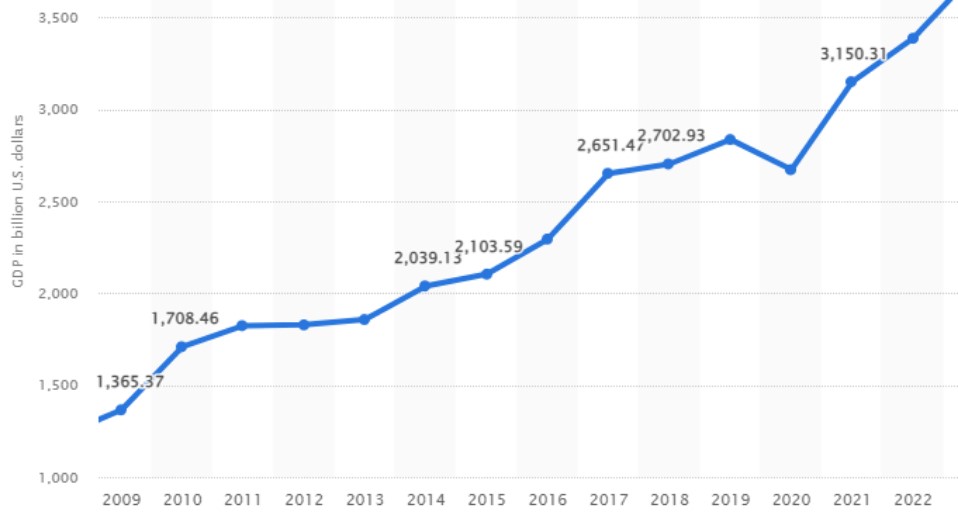

From the election of current prime minister Narenda Modi until the most recent available statistics (2014–2022), and taking the lockdowns into account, the average annual compounded growth rate was 6.7 percent in rupees and 4.9 percent in dollars. For the two post-lockdown years 2021-2022, the respective figures at 8.0 percent in rupees and 5.2 percent in dollars. Rising inflation and a potentially widening current account deficit are risks that the investor should bear in mind for the future outlook.

According to data and calculations by the World Bank, the Indian economy grew at an average annual compounded rate of 6.9 percent from 2009 to 2014 and 7.4 percent from 2014 to 2019 (after Modi’s election and before the government-imposed lockdowns) in Indian rupees. The above figure illustrates the corresponding figures in U.S. dollars, specifically a growth rate of 5.3 percent from 2009 to 2014 and 6.0 percent from 2014 to 2019.

It is therefore clear, and generally acknowledged, that India’s GDP has shown strong growth in recent years. It expected to grow further in the coming years. More money is circulating, and businesses are in general doing well.

For about India in greater depth, please subscribe. You will receive access to two subscription-only articles every week. This week, those two articles will continue the discussion of Indian equities in general, and in particular, more intensively and in greater technical and fundamental detail.

The Indian market and some Indian companies are tradeable on the New York Stock Exchange, the Euronext exchange, and many European and other international bourses. Available instruments include index funds for both the Sensex and the other principal index, the Nifty, which is the principal index for the National Stock Exchange (NSE). Sector-specific and other limited-coverage ETFs; and American Depository Receipts (ADRs) in both New York and Europe, as well as direct stock purchases.

Both the Sensex and the Nifty are index weighted by market capitalization. The Nifty is more distributed than the Sensex, however, comprising 50 rather than 30 stocks. The Nifty also has a broader sectoral representation, whereas the Sensex is weighted towards the energy and financial sectors. Some major companies, such as Reliance Industries, are listed on both exchanges. Long story, short: The Nifty is less risky and more comprehensive than the Sensex, while the Sensex is more liquid but also potentially more volatile than the Nifty. ETFs are widely available that focus on one or the other, as well as on various specific economic sectors.

The present article and its subscription-only supplements are prospectively the first in a series of weekly surveys of different equity markets in Asia, which I used to cover for the old Asia Times Online, prior to its current reincarnation. That doesn’t have to be the case, however. What I write about will depend upon the feedback I get from you, the readers. For example, next week I will probably write about the gas market in Europe and its sources for foreign imports.

Indeed, this venture will live or die depending upon you, the subscribers; so I am genuinely interested to know in which directions you think I should go. You can reach me at Robert@hilltowerresourceadvisors.com with your ideas. Even if I cannot respond to each of you individually, I will mention here the trends in your replies, so that you can help me decide what to write about.

Other possibilities include more on India, drilling down even deeper and discussing particular sectors or companies; or other Asian equity markets; or broader geoeconomic issues such as the impact on Europe of Russia’s war against Ukraine, or energy security in Europe and Eurasia, or its particular regions and countries; and a host of other topics. There will probably be a lot more global energy and mining coverage, since that’s one of the things I’m best known for. Of course, fast-breaking events can also form the basis for new and timely analyses. Thanks for reading, and I look forward to enjoying the ride with you. Please be in touch.