Global oil markets are still functioning as planned, fully absorbing the possible negative effects of Western sanctions on Russia. Moscow’s ‘Go East’ strategy appears to be nullifying the still largely ineffective sanctions imposed by most OECD countries, led by Washington and Brussels. While Russian hydrocarbon revenues have been impacted, the expected financial squeeze on Moscow meant to hurt the Russian war machine is weak. China and India, Asia’s main oil and petroleum product customers, are taking advantage of the premiums offered by Moscow. Global oil markets are still uncertain about the direction in 2024, with a possible economic crisis in the West and East looming on the horizon. Reports indicating negative global oil demand in November have dampened bullish sentiments.

US oil exports continue to record levels in recent months, but others are feeling the negative fallout of lower-than-expected demand growth or Russia’s push to gain market share. Recent reports suggest that Moscow has surpassed Saudi Arabia as the biggest supplier to China. In 2023, Moscow pushed OPEC exporters to the back, reaping the rewards of its oil market strategy amid a continuing geopolitical shift. In 2023, Moscow pushed OPEC exporters to the back, reaping the rewards of its oil market strategy, while getting additional support from the continuing geopolitical shift. Beijing and Moscow have clearly increased their cooperation, not only in the energy sectors but also militarily and economically. Beijing, and its cohort North Korea, have thrown a lifeline to Moscow’s leader Putin; without China, Russia’s onslaught on Ukraine would already have been minimized.

For OPEC, the Russian and American oil market share push has come as a surprise, as the oil group is fighting an uphill battle not only to stabilize global markets and prices but also to regain part of its market share. Until now, on all fronts, OPEC leaders Saudi Arabia and UAE are not looking very successful. While Riyadh has unilaterally taken on its perceived position as a market maker or swing producer by removing millions of barrels out of the market, the UAE’s Abu Dhabi keeps to its agreed export volume levels; others are not willing to comply fully or not even able to produce up to quota levels. The so-called oil cartel is definitely on the receiving side, which is still hard for some to grasp.

In 2023, China imported 107 million tons of crude from Russia, almost 25% more than in 2022. At the same time, Saudi Arabia, which is still pushing multibillion investments in China, has been left with not even 86 million tons. The hard facts are right now that Russia is China’s main oil supplier, delivering around 2.15 million bpd. Most analysts agree that the main fundamental reason behind this Russian push is the fact that Moscow offers major discounts to clients. Saudi’s move to cut unilateral production, even almost hitting Corona-period levels, has not brought the targeted results set by the strategists in Riyadh. At the same time, Russia has been eating into the still existing market share in Asia, hitting Arab and African suppliers, but not Putin’s ally Iran extremely.

Signs of pressure on the Saudi position are clear but fully denied by Riyadh’s leading pack. OPEC’s unofficial leader, and most vocal proponent of the current strategy, Prince Abdulaziz bin Salman, the minister of energy, repeats the known riddle of market stabilizer, not interested in geopolitics, while being optimistic about the future. The future, however, also for cash-rich Saudi Arabia, depends on hydrocarbon revenues in the end. Volumes don’t speak the language of paying for the government budget or the still-growing list of Giga projects in the Kingdom.

While analysts are continuously repeating Saudi’s break-even price or the expected price floor of around $75 per barrel, the latter is just an accounting tool used by experts to make a point. Economics are different, especially if total costs of entering global financial markets are almost zero. The latter, however, is changing, also for rentier-states such as Saudi Arabia. Costs are up, interest rates globally are putting pressure while the risk of economic turmoil in China or even India is not unrealistic anymore.

Things will have to change to bring the Saudi government budget again into an ultra-green safe zone. Until now, Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman is still playing markets and geopolitical power plays as he sees fit. Becoming the Middle Kingdom or Power is the ultimate goal, being the power broker between the West (USA, UK, EU), the East (China, India), and Russia. The costs of keeping all of them as a friend are, however, piling up in the last months. Saudi Arabia’s diversification is ongoing, with unexpected success rates, but budgets are still hydrocarbon-driven.

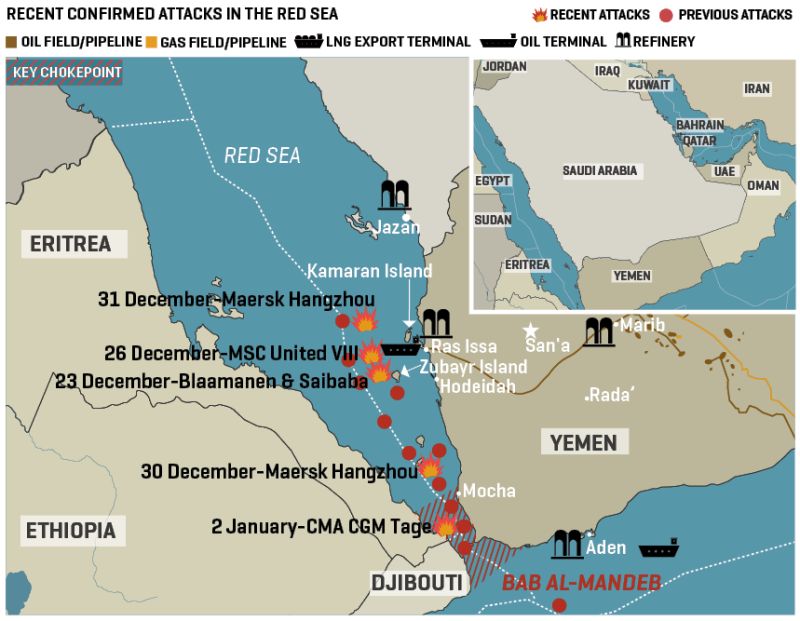

Being hit by lower global prices and a loss of market share is going to remove the silver lining of the bromance with Moscow. Major scratches are clear, but the current Houthi-Red Sea crisis and a potential re-emerging military clash with Iran in the east of the MENA region, is not to the liking of MBS and the Saudi regime. The preferential position that Russia currently has in the crisis, as its crude oil and LNG vessels still can cross the Red Sea-Bab Al Mandab arena, is not to the liking of Arab OPEC producers. While Saudi Arabia and the UAE are facing higher costs in maritime trade or even are blocked totally, Russia can supply Asian markets still without any threats.

The costs of the friendship are piling up; the main question at present is when Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman and his brother are going to make the call to either push Putin to cut a large chunk of his current export volumes or to call for divorce? While analysts expect another round of OPEC+ cuts in Q1, based on official statements made by OPEC officials, keep in mind OPEC is not a company but a conflagration of independent and mostly obnoxious regimes, holding “Nations First” strategies above all.

Riyadh, without addressing Russia’s market success, may put the blame on regional instability and threats to its overall economy, making Houthi, Hezbollah, and Iran easier targets than Putin. As Saudi Arabia looks at its future, committing to finance Russia or allowing the Moscow-Beijing axis to grow could be more costly than a divorce. A call for a change in the relationship is expected, considering the need for income for Vision 2030 and regional military capabilities.